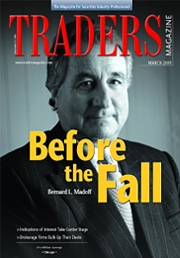

The abrupt closure of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities in December marked an ignominious end for a firm that, after nearly 50 years in business, enjoyed near universal respect on Wall Street, as well as major financial success. That its founder could be charged with defrauding its customers out of billions of dollars, as two arms of the federal government have alleged, shocked and dismayed those who know the man.

He was considered a leader in the stock trading business who almost single-handedly created the modern-day Third Market for retail orders by attracting order flow destined for the New York Stock Exchange.

His ability to anticipate punishing regulatory changes designed to sideline market makers, coupled with a commitment to spending on technology and sophisticated inventory management techniques, enabled him to survive and prosper whilst many competitors fell by the wayside.

His knowledge of the intricacies of market structure and his openness with regulators, legislators, journalists, academics and industry executives served to boost his profile and influence. Those relationships also didn’t hurt his market-making business.

In 1982, after more than 20 years in business, Madoff reported $5.5 million in net capital, making his the 153rd-largest brokerage house. He had 35 employees. By January 2007, he reported $613 million in net capital, making his firm one of the 40 largest. He employed 146 people.

His close ties to Nasdaq from its early days and their shared interest in wresting market share from the Big Board translated into a win-win for both parties as Madoff’s Third Market business grew. His participation on NASD committees and his unwavering support for many of Nasdaq’s often dealer-unfriendly initiatives through the years only cemented the bond.

By the 1990s, Bernie had become something of a senior statesman in the industry, serving on the NASD board, as non-executive chairman of Nasdaq and as head of the Securities Industry Association’s influential trading committee. For a while, he was spending one-third of his time in Washington as an unofficial lobbyist for the dealer community. Madoff was often quoted in the press.

On a personal level, he was almost universally liked. He was open. He was helpful. He was willing to share his knowledge of market structure with almost anyone. The same could be said of all four Madoff principals, including Bernie’s younger brother Peter (his number two) and sons Mark and Andy. “You couldn’t say enough nice things about them,” Jack Hughes, a former head of trading at Madoff customer Janney Montgomery Scott, said in a typical response. “They were just great, great people who would do anything for you. And if you had a question, they would always take the time to answer it.”

Competitors’ View

Not everyone saw eye to eye with the Madoffs. They championed regulatory initiatives that squashed bid-ask spreads and angered fellow market makers. Many are now quick to suggest that the profits Bernie generated through his alleged Ponzi activities made it easier to stomach those spread-narrowing changes. As Madoff’s power grew, so did the resentment. His detractors said he was arrogant. Some said he could talk a good game but couldn’t always deliver.

Through his attorney, Bernie declined to speak with Traders Magazine for this article. Peter, Mark and Andy also declined comment.

Bernie wasn’t the whole show at BMIS. Peter had joined the firm in 1965 while still a student at Fordham Law School, from which he graduated in 1967. Peter was the firm’s original computer whiz and eventually assumed responsibility for the trading operation. It was Peter, in fact, who saw the potential in trading securities listed on the New York Stock Exchange. And it was that decision that catapulted the firm into the big leagues of wholesaling.

The second generation-Bernie’s sons, Mark and Andy-took control of the trading desks in the 1990s. As the years passed, the two MBA’d brothers largely replaced their father and uncle as the faces of the firm through their work on committees and appearances at industry conferences.

Mark and Andy were on the desk five years ago when it came time to usher in the black-box era-the use of computers to make markets, hit bids and lift offers. That forced the redundancy of a good swath of the firm’s traders.

The decision was unavoidable but perhaps came too late. For all the firm’s savvy, it was being out-traded by a new breed of algorithm-toting market maker. Madoff lost market share and profits. In the end, an investment bank could find no buyers for BMIS, and the firm was disbanded.

In the Beginning

Ironically, the circumstances behind the fall of Madoff’s wholesale business were exactly the same as those behind its rise. The business crashed in the 2002-2008 period after the powers that be in Washington forced the industry to trade in penny increments. The firm got its foot in the door in the 1960s after the Securities and Exchange Commission forced the over-the-counter industry to automate its quotes.

Spurred on by a U.S. Congress upset by dirty dealings at the American Stock Exchange, the SEC spent two years analyzing the inner workings of the securities industry. In 1963, it produced the seminal “Special Study of the Securities Markets,” which concluded that changes were needed.

One of its criticisms was directed at the sprawling over-the-counter market and its lack of transparency. Quotes were only published once a day in the Pink Sheets and typically out of date by the time they reached traders’ desks in the morning.

To do a trade, a broker would have to telephone three market makers. The process was slow, inefficient and did not take into account all of the possibly 15 to 20 dealers bidding for or offering stock. Consequently, with no intraday transparency, bid-ask spreads were wide and market-maker profits flowed to just a few big New York wholesalers.

Displaying quotes once a day was insufficient, the SEC concluded. It believed computer technology was advanced enough to support widespread intraday quote dissemination. It urged the NASD to investigate the possibility.

At the time, BMIS was a small and struggling wholesaler, finding it difficult to make headway against larger and more established competitors. Eager to compete based on the quality of its quotations, the firm was often ignored by other dealers. Often as not, Madoff’s firm did not get called when there was business to do.

The over-the-counter market in the 1960s was dominated by large New York-based wholesalers. These are brokerages that maintain inventories in securities and fill orders for other brokers. The top wholesalers of the day included Troster Singer, Singer & Mackie, New York Hanseatic, J.F. Reilly and Eastern Securities. Wirehouses such as Merrill Lynch did run OTC desks, but their presence was negligible.

So when the NASD was tasked with developing a quote display system that could be installed in dealing rooms around the country, Madoff saw the potential. “We felt, as a small market-making firm, it would level the playing field for us,” Madoff told author Eric Weiner for his book “What Goes Up: The Uncensored History of Modern Wall Street.” “So we pushed that concept, and I was not particularly popular with my competitors.”

With all quotes displayed in one place throughout the day, market makers would have to do business with those displaying the best prices, no matter who they were. That would give a newcomer like Madoff a fighting chance. It would also cut into the business of the dominant players.

The NASD set up an automation committee in 1964, the year after the SEC report came out. It was chaired by Robert “Stretch” Gardiner, head of Reynolds Securities, and staffed with executives such as Johnny McCue, from Baird & Co., a regional broker, and Joe Fuller, from J.B. Maguire, a Boston wholesaler. Madoff was not on the committee.

Seven years later, after much kicking and screaming by traders, the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation system, or Nasdaq, finally launched. Credit is given to the now-deceased Gordon Macklin, Nasdaq’s first president, for making it happen.

In the end, Nasdaq did what they thought it would. It brought quotes to the surface and competition to the market. Small wholesalers such as BMIS and J.B. Maguire and regional brokers such as Baird got a seat at the table. Spreads narrowed. Large wholesalers including Singer & Mackie saw their margins squeezed.

“Nasdaq gave those relative unknowns a sort of instant prominence,” Singer & Mackie executive vice president Robert Mackie Jr. told Financial World magazine in 1973. “If they make the best market on that machine, people are bound to do business with them. Before Nasdaq, there was no way for the small firm, except through a strenuous effort, to get itself known as a market maker.”

For Bernie, it was never a just one-way street. He got from the NASD, but he also gave back. The former head of trading from a large New York firm remembers Bernie “always made himself available in the early days of Nasdaq when it was hard to get volunteers. He was always willing to be involved in a committee or to help out somehow. After a while, he became a leading voice and was influential and valuable to Nasdaq.”

Another ex-head of trading at a large New York firm who participated on NASD committees agreed. “Bernie’s strategy was to get actively involved in all aspects of the industry,” he said. “He had a much bigger presence than the size of his firm would naturally warrant. By being visible, he’d boost his business. They never said no. They volunteered for everything. It was a very smart move.”

Third Market

Nasdaq brought scores of market makers out of the woodwork and onto the desktops of Wall Street. The transparency benefited Madoff, but his firm was now one of about 500 quoting prices in OTC stocks. The competition was fierce. Was there a way to set himself apart?

Sometime in the early or mid-1970s, Peter Madoff became enamored with the idea of trading NYSE-listed stocks. Because of the active market in these securities on the floor of the New York, they were much more liquid. That made them easier and safer to trade.

OTC names were much riskier. “That was pretty much one-way order flow,” a trading executive noted. “If there were no more buyers and if you were a market maker, you became the buyer.”

In addition to the stocks’ lower risk profile, NYSE rules also lent appeal to Madoff’s idea. NYSE Rule 390 prevented NYSE members from trading NYSE-listed securities on a principal basis away from the exchange. That eliminated many potential competitors to Madoff, as most firms of any size were Big Board members. The rule did allow them to send their NYSE orders to other exchanges or market makers. Most of Madoff’s competition would come from NYSE and regional exchange specialists. Madoff was not, of course, a member of the New York.

The business of trading NYSE-listed securities outside the confines of the exchange was known as the Third Market. Until Madoff dived in, the business was largely institutional. It was dominated by firms such as Weeden & Co., First Boston and Blyth & Co. Some wholesalers did offer retail brokers a Third Market service in the 1960s, but with the exception of Weeden, none was especially large. Others were A.W. Benkert and American Securities.

Madoff started trading NYSE stocks on a small scale in the mid-1970s, at a time when the industry was embroiled in a contentious debate over regulatory changes that would make it easier for brokerages to compete with NYSE specialists. The SEC wanted to foster widespread trading of NYSE names outside the exchange’s four walls. The U.S. Congress, via the 1975 Amendments to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, gave them the authority to do so.

The SEC’s dream was to break up the Big Board’s monopoly in the trading of its securities by fostering the development of a central market system. The agency’s original idea involved a consortium of OTC dealers and exchange specialists competing against each other for orders. As early as 1965, an SEC staff study concluded the NYSE’s Rule 394 (later Rule 390) shielded Big Board specialists from competition.

The plan to construct a central, or national, market system boiled down to two competing ideas. The Cincinnati Stock Exchange was proposing a Composite Limit Order Book (CLOB) known as the Multiple Dealer Trading System, within which all trades would take place. The New York Stock Exchange was promoting the Intermarket Trading System (ITS), a routing and quoting network that would link all the exchanges.

The Cincinnati’s CLOB, based on a trading platform designed by Weeden principals, was perhaps the more radical of the two ideas and eventually lost the SEC’s endorsement. The ITS launched in 1978 with the participation of every exchange except the Cincinnati.

Cincy

The ITS was a godsend for Madoff if only he could plug into it. The network was a critical link to the New York Stock Exchange that would allow NYSE specialists to see and access the quotes of regional exchange specialists. In turn, it would allow regional specialists to access the New York to lay off their positions.

Madoff, however, was not a regional specialist. He was an NASD member. And when the ITS launched, there was no connection to Nasdaq. That was not for lack of trying on the part of the NASD. The New York fought hard to keep the NASD out. It wasn’t until 1982 that the NASD was permitted to link to the ITS, and even then, market makers could only trade a limited number of (Rule 19c-3) stocks over it.

So in the late 1970s, the Madoff brothers started sniffing around the Cincinnati, hoping to become specialists. Although they were eventually allowed to purchase seats and Peter took a position on the board, they were initially treated with suspicion. Cincinnati executives were worried Bernie might be some kind of spy for the NASD, which was fighting hard to get full access to the ITS. In 1978, Bernie was a member of the NASD’s National Market System Trading committee. In 1979, he was on the NASD’s National Market System Design Committee. From 1981 to 1983, he was the head of the design committee. In 1983, he became chairman of the NASD’s District 12 Committee, representing the New York area.

For the Cincy, the fear was very real. If the NASD did get full access to the ITS, and all those market makers started trading NYSE names, there would be little reason for regional stock exchanges to exist. Imparting precious technical information to the Madoffs could prove hazardous.

In any event, by 1980, the Madoffs were members. Peter joined the trading and technology committees, and the firm–along with other CSE specialists such as Merrill Lynch–had invested in an upgrade of the MDTS. That year, the Cincinnati closed its floor and opened for business as the country’s first all-electronic stock exchange. In 1981, when the exchange finally won access to the ITS, Madoff could hang out his shingle as a full-fledged alternative to the New York Stock Exchange.

ITS Access

The ITS was terrific for Bernie,” said Don Weeden, former CEO of Weeden & Co. “They were able to get their markets in and change them very quickly. They were very competitive with the New York and the other regional exchanges. He did very well doing that.” (Weeden and Madoff are often considered in the same light, as both men took on the New York Stock Exchange in David-and-Goliath fashion and both invested heavily in technology to do so.)

While it never succeeded in becoming the central marketplace backers like Weeden and the SEC had hoped, the Cincinnati did retain a special standing in the eyes of the SEC.

One former Cincinnati specialist recalled that the rules of the exchange permitted maximum quote widths of 25 cents in the early 1990s, and so that was how he programmed his system. That got him a call from Peter Madoff, who asked the specialist to narrow his spreads. Madoff said the Cincinnati was always under scrutiny from the SEC and was held to a high standard. Tighter spreads would prove to the industry that the Cincinnati was “real” and its quotes accessible, Madoff explained.

Bernie would later tell Traders Magazine: “The Cincinnati has done a better job than the other regionals in keeping their market makers in a competitive mode. We set the standard at the Cincinnati.”

The Customers

Now that Madoff had the ability to trade listed stocks, he set about the task of acquiring a steady stream of order flow from retail brokers. He won Charles Schwab & Co.’s business in short order, but the majority of brokers proved a tough slog. The business didn’t really pick up until after the 1987 stock market crash.

During much of the 1980s, one source believes, the mainstay of Bernie’s business was arbitraging the prices of OTC stocks with those of their attached warrants. Because the Black-Scholes options pricing model had yet to be fully understood by the Street, making money on the “optionality” of warrants was easy pickings. In those days, many speculative issuers, such as technology companies, would tack on a warrant to a new issue as a sweetener for the investor. The warrant was exchangeable into a certain number of shares at a certain price.

“The third market was almost a side business,” this former trader said. “Bernie was very big in that [warrants] business, along with about four other firms. You could see. You would offer size, and Bernie would step up and buy it. Then he would be out there doing a contra trade in the common.”

This source believes that the warrant trading operation was done under the aegis of Madoff’s investment management operation, which allegedly eventually became a Ponzi scheme; and that losses in this warrant trading activity may have led to Madoff covering losses via the Ponzi scheme. “He had more share than you would expect a firm his size to have in those warrants,” the source said.

Whatever the case, Madoff still had high hopes for his Third Market business. And because he had hopes of becoming a volume player, he decided he needed to automate the intake of orders. That way, brokers could send him flow at the push of a button and receive their trade reports just as quickly. This was a big and expensive project. One exec estimated it cost firms that chose to do this between 25 and 40 percent of a year’s profit-and-loss account. Peter Madoff was put in charge.

In 1983, Madoff brought in TCAM Systems, a software vendor started in 1979 by the former chief information officer at Smith Barney, to build the system. TCAM had built a similar system a year earlier for Dean Witter Reynolds’ OTC department.

The system TCAM would build for Madoff would read the quotes from the newly launched Consolidated Quotation System and quickly execute incoming orders at prices based on those quotes. The project took five years to complete. When it was finished, in 1988, it automatically filled orders of up to 3,000 shares at the national best bid or offer in less than 10 seconds. That was considerably faster than the New York Stock Exchange, which, by rule, had 90 seconds to handle the order.

“He was a pioneer,” said Ken Pasternak, former chief executive of Knight Capital Group and a competitor to Madoff in the Third Market from the 1990s. “What helped him was the fact that he was the first to automate and provide [speedy] executions.” Pasternak ran trading at Troster Singer in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Troster automated the intake of its OTC flow at roughly the same time Madoff automated the intake of his listed flow, Pasternak said.

Other industry execs also acknowledged Madoff’s technology prowess. “They always had the best technology,” Dennis Green, the former head trader at Legg Mason, remembered. “They always did. Even when none of us could afford that technology. It was expensive for us in the hinterlands. Maybe not in New York. But they always had the best systems.”

Madoff’s speedy fills involved trade-offs, though. An order sent to the New York might get filled at a price better than the NBBO, or within the spread. Madoff offered no such “price improvement.” But, he argued, since he traded only the most liquid stocks, their spreads were as tight as they could be. Thus there was little chance they would get price improvement at the Big Board. Still, the criticism over Madoff’s lack of price improvement would dog him throughout his career.

Madoff’s business plan was simple: Accept orders only in the biggest, most liquid stocks from “uninformed” retail investors. Charge no fees. Guarantee fills on all orders up to 3,000 (later, 5,000) shares. Execute orders faster than the New York Stock Exchange.

Restricting his dealings to retail flow and the most liquid stocks would mitigate Madoff’s risk. So-called uninformed investors-in contrast to professional traders-know less about a stock’s immediate prospects than the dealer. And with the most liquid stocks, laying off positions would be easier.

Madoff got his new TCAM system installed just in time. The stock market had crashed the previous October, and the public had deserted the market. Retail brokers were hurting and looking for ways to cut costs.

Orders sent to the New York incurred both exchange fees and specialists’ charges. Madoff, on the other hand, charged no fees. That was part of his appeal. Prior to the Crash of ’87, NYSE member firms balked at sending their orders to Madoff out of loyalty to the exchange or fear of retribution. Afterward, those qualms vanished.

To sweeten the deal, Madoff started paying brokers for their flow. That made it even harder for cash-strapped brokers to resist the trader’s entreaties.

“If you sent it to the floor of the New York, you got charged for it,” Green explained. “If you sent it to Madoff, they paid you. For many, it was a no-brainer.”

Hard Times

With hard times on Wall Street, the Third Market began to take off. According to a Wall Street Journal report, the share of trades in NYSE-listed securities under 1,100 shares done in the Third Market tripled between 1984 and 1989 to 6 percent. BMIS accounted for 70 percent of that figure, according to estimates of the exchanges. The surge left the New York Stock Exchange with only about 66 percent of all trades in its stocks, down from 87 percent in the late 1970s.

“The New York Stock Exchange looked at them as serious competitors,” remembered Chris Keith, the Big Board’s former chief technology officer and a member of the exchange’s executive committee from 1980 to 1988. “The Madoff name was well known at the exchange and the firm was a not infrequent topic of discussion in meetings. He was highly regarded.”

Meanwhile, over at the NASD, Bernie had reached the apogee of his relationship with the organization. In 1986, he was elected to the board of governors along with 39 others. He was also on the executive committee, the board surveillance committee and the long-range planning committee. He was chairman of the NASD’s international committee, too, having recently opened an office in London to trade ADRs.

After more than 25 years in the business, everything was finally falling into place for Madoff. In 1989, the firm had 20 traders dealing in the top 250 NYSE-listed names. It was handling about 15,000 trades per day, totaling about 5 million shares. That gave it 2 percent of the share volume in NYSE-listed securities. By the end of the decade, BMIS boasted 100 customers including regionals such as A.G. Edwards, Dain Bosworth and Rauscher Pierce and discounters such as Schwab, Quick & Reilly and Fidelity.

For the most part, BMIS had the growing market to itself, but that would not last. In 1985, a veteran manager at several wholesalers started a small third-market dealer in White Plains, N.Y., called Trimark Securities. Steve Steinman, Trimark’s founder, had held trading positions at a number of firms, including Troster Singer and M.H. Meyerson. Trimark was not much of a factor in the late 1980s, but was digging in. In 1990, the dealer signed an agreement with TCAM to build a trading system.

Madoff didn’t have all the retail flow not going to the New York Stock Exchange. Discount brokers such as Schwab and Fidelity also operated specialist posts at various regional exchanges to internalize their NYSE-listed orders. Pershing, a large clearing firm, also operated specialist posts at regional exchanges.

Payment for Order Flow

Market making in those days was still a spread game. The minimum trading increment was a relatively fat 12.5 cents per share, allowing dealers to make a profit buying at the bid and selling at the offer. The wide spread also enabled them to pay for order flow. The practice had been around since the 1970s, when wholesalers were paying brokers about 2 cents a share for their OTC orders. Madoff extended the practice to NYSE-listed securities in 1988, paying brokers about a penny per share.

The move did not endear Madoff to the New York Stock Exchange and some of the regionals. As BMIS began to eat into their businesses, they complained bitterly to the SEC. They charged that Madoff’s firm competed unfairly because it was not bound by the rules of exchanges. BMIS could pick and choose with whom it traded and which orders it would accept. Exchanges, on the other hand, had to take on all comers.

Others contended the SEC should abolish payment for order flow, as it constituted a perverse incentive for order-flow senders. Brokers should choose their trading venues based on best execution, not kickbacks, Madoff’s detractors argued.

Madoff countered that the point was moot because his customers always got the best bid or offer. In addition, the brokerage could pass the savings on to its customers.

Ray Pellechia, an NYSE Euronext spokesperson for many years, still maintains that PFOF is harmful and that investors deserve a shot at price improvement. He recently blogged: “I also believed-and still do-that pay for flow deprived investors of the opportunity to get the best price; that is, the ability to trade at a price better than the published best bid or offer.”

The SEC had long tolerated payment for order flow. But it was still concerned over possible conflicts of interest. In July 1989, the SEC convened a roundtable of industry leaders to discuss the issue. Bernie Madoff, the NYSE’s Dick Grasso, Charles Schwab, Leslie Quick of Quick & Reilly, John Watson of the Security Traders Association, Peter DaPuzzo of Shearson Lehman and Buzzy Geduld of wholesalers Herzog Heine Geduld all sat down to offer their views on the subject.

After listening to all the arguments, the SEC still took no action. The sniping continued unabated for at least five years. Eventually, Congress waded in.

In the spring of 1993, Congress held hearings on the issue. NYSE chairman William Donaldson testified, asking Congress to ban the practice. So did NYSE president Dick Grasso. Bernie testified in defense of the practice, but said he would be open to brokerages having to disclose the practice. NASD president Joe Hardiman testified in support of the practice, defending the Madoff model.

By this time, however, the approaches of the competitors had moved closer together. The New York began offering rebates, and Madoff began offering price improvement. The exchange paid order senders $1.60 per order if the order came through DOT and was between 100 and 2,099 shares. Madoff, if the customer requested, would stop the trade at the NBBO and then expose the order to the market over ITS for one minute to try and get a better price.

Still, after Congress took a look at the issue, the SEC followed with some disclosure rules. First proposed in October 1993, they became law in 1995. From then on, brokers would have to inform their customers if they were paid for their orders.

Despite the black eye Madoff got from the payment for order flow issue his firm was on a roll. In 1992, BMIS was doing business with 350 NYSE members and trading 9 percent of NYSE-listed volume. The firm employed 40 traders and was processing 20,000 to 25,000 trades per day. In January 1993, BMIS reported net capital of $86.5 million, making it the 70th-largest firm on Wall Street.

The Madoffs’ ties to the NASD were as strong as ever. In the early 1990s, Bernie became chairman of the Nasdaq Board of Directors. The title was largely honorary, as Nasdaq was not yet an entity in and of itself, but it did confer certain advantages. In 1993, Bernie was a member of the NASD’s strategic planning committee and the international committee. Also, in 1993, Peter Madoff was elected to the NASD’s board of governors. Peter also joined Nasdaq’s board of directors for at least three years.

While honorary, Bernie’s position as Nasdaq chairman did allow him to fight for causes near and dear to him under the cloak of the NASD. He spent much of his time in Washington during those years, becoming a familiar face in the halls of Congress. “You can’t underestimate the influence the Madoffs had on the regulators and the legislators,” one former trading executive noted. “They worked very hard at it for 30 years. They spent a lot of time and money securing those positions and relationships. You would see a senator or congressman show up at one of our industry things, and they just walked up to him and spoke like old buddies.”

One of the battles Bernie chose to fight involved access by Nasdaq dealers to the Intermarket Trading System for the trading of non-19c-3 stocks. Market makers had had a link to the ITS via Nasdaq since 1982, but were only permitted to use it for trading 19c-3 stocks-stocks that had come public after April 1979. Bernie and the NASD wanted the ITS Operating Committee to extend access to all NYSE-listed names.

At this time, BMIS was still one of the few Nasdaq market makers trading listed stocks off-board. Although it could access the ITS from its perch at the Cincinnati, the ability to trade all NYSE stocks from a single operation had obvious appeal. It would eliminate the need to maintain two systems and membership in two organizations.

In 1991, the ITS Operating Committee denied the NASD’s request. Madoff petitioned the SEC to intervene, but to no avail. It would be another eight years before Nasdaq dealers would gain full access to the ITS.

Next Nasdaq

Despite Madoff’s closeness to the NASD, the relationship had its limits. In the mid-’90s, Nasdaq made its first attempts to transform itself from a communications system for market makers into a quasi stock exchange. In swift succession, it proposed building three CLOB-like systems-N*Prove, Naqcess and Next Nasdaq.

Market makers hated the ideas. They complained the systems would come between them and their customers as they would permit brokers to post limit orders directly on a Nasdaq system. Nasdaq was trying to compete with them, they argued.

The battle raged between the NASD and the dealer community from 1995 to 1998. Madoff was a key representative for the opposition after becoming one of two vice chairmen of the Securities Industry Association in 1996. He was to head the SIA’s influential Trading Committee for the next two years, leading the negotiations with the NASD. N*Prove didn’t pass SEC muster. Naqcess was shelved. Next Nasdaq went to the SEC for approval, but in the end, it too died, thanks partly to the effort by Madoff.

OTC dealers won the battle against Nasdaq’s early CLOBs, but they were not destined to win the war. One year after defeating Next Nasdaq, the exchange-to-be introduced another CLOB called Supermontage. This one stuck.

Back in the mid-’90s, the tide was already turning for market makers. They incurred the wrath of the regulators after studies done by two academics implied they were colluding on prices. Both the SEC and the U.S. Department of Justice launched investigations into price collusion after two university professors discovered market makers did not quote in odd eighths. A settlement resulted in about two dozen market-making firms (excluding BMIS) paying $1 billion in fines. The industry also got a tough new rule requiring dealers to display their customers’ limit orders.

The brokers quietly paid the fines but resisted the SEC’s proposed Limit Order Display Rule. Market makers fretted that the competition it would introduce would cut spreads and profits. At least three wholesalers-Herzog Heine Geduld, Mayer & Schweitzer and Sherwood Securities-made a last-ditch appeal to Congress to block the SEC from passing the rules. The campaign failed, and in 1996, the rule was approved.

In contrast to many of his competitors, Madoff appeared unperturbed by the rule, part of a package of rules called the Order Handling Rules. He described it as a boon for the Nasdaq market. In a letter to the SEC dated Jan. 12, 1996, Bernie and Peter Madoff maintained the rule would help “achieve price discovery and fairness to investors.” A year later the pair was still upbeat, telling Traders Magazine the rule would increase liquidity for Nasdaq securities.

Why was Madoff upbeat when many of the other dealers were pessimistic? Wouldn’t smaller spreads cut into Madoff’s profits as well? Apparently not. BMIS had moved beyond spreads.

Spreads were “a thing of the past,” Bernie told Traders Magazine in January 1997. “You’re making it today on trading,” he said. “Everybody would love to sit there with a market 20 to 1/8 and buy at 20 and immediately sell that at 20 1/8. That almost never happens.”

Somewhere along the way, Madoff’s firm had moved from “flipping for eighths”-as the dealers used to call it-to holding positions for longer periods. The trader was incorporating more risk into his operations. “We’re a position trading firm,” Bernie would later tell Traders Magazine. “We’ve always traded with a large inventory. It is larger, I believe, than most, if not all, of our competitors’. We have the ability to hedge our risks.”

He explained: “In order for us to provide a better execution than our competitors, we must expose ourselves to greater risk by carrying inventory and being willing to provide liquidity.”

By 1997, it had become obvious (to Madoff, anyway) that the old market-making model was not sustainable. Making a profit by buying at the bid and selling at the offer only worked if the minimum trading increment was wide enough. Decimalization was on the horizon, and the future of the bid-ask spread was not promising.

A former competitor notes that Madoff was always preparing for the future. “We were on a lot of committees over the years,” ex-Knight CEO Pasternak said. “We always thought market transparency, Manning (limit order) protection and decimal pricing were inevitable. The real secret to success was to figure out where the market was going and position yourself.”

For 200 years, the minimum increment had been one-eighth of a dollar, but the days of that custom were numbered. As early as 1991, the SEC was mulling a move to penny ticks. In 1994, the SEC’s Division of Market Regulation recommended the industry move to sixteenths as soon as possible. Spreads were headed in only one direction: down.

In December 1996, Nasdaq’s Quality of Markets Committee voted to cut the minimum spread by half and move to sixteenths. It also voted to study trading in decimals. In March of the following year, the Nasdaq board voted to quote in sixteenths. In May 1997, both Trimark Securities and BMIS started quoting NYSE names in sixteenths, a month before the New York Stock Exchange. Spreads did indeed collapse in June 1997.

That same month, the New York announced it would move to quoting in pennies by 2000. Decimalization, Madoff told Bloomberg News in 1997, didn’t necessarily mean brokerage profits would suffer. “Decimals will encourage more trading,” he said, “and the greater volume could more than compensate for narrowing spreads.” Decimal trading would debut in 2001.

Knight/Trimark

Narrower spreads weren’t the only challenge Madoff faced in the late 1990s. Trimark Securities, previously a bit player in the Third Market, was coming on strong. Carried by the bull market of the 1990s, partly fueled by America’s newfound passion for online trading, Trimark would eventually pass Madoff in market share terms.

In 1994, the suburban New York dealer was taken over by a trio of brokerages and executives from wholesaler Troster Singer. The following year, the firm’s chief executive, Steve Steinman, became one of the four founders of Roundtable Partners, from which the formidable Knight/Trimark wholesaler would emerge. The firm would come to dominate the wholesaling business, thanks to order-flow arrangements with about two dozen retail brokerages that invested in Roundtable. In contrast to Madoff, Trimark traded all 2,500 or so NYSE-listed securities, not just the biggest, and welcomed flow from informed traders as well.

By the end of the 1990s, according to the NASD, Trimark was the largest off-board trader of NYSE-listed securities, with 46 percent of the third market. (The data include the institutional end of the third market.) In December 1999, Trimark traded about 53 million NYSE-listed shares per day, up from 11 million in January 1997.

The business of processing small orders in NYSE-listed securities had by now coalesced around three groups. The New York largely held onto the flow from its largest members, such as Merrill Lynch and Smith Barney. Trimark, Madoff and the Chicago Stock Exchange vigorously competed for the business of discount and regional brokers. Finally, a few of the retail brokers, including Schwab, Fidelity and Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, internalized their flow on various regional exchanges.

Stiff competition from Trimark and the Chicago kept BMIS on its toes. Trimark, for instance, turned up the heat in June 1999, when it became the first market maker to guarantee price improvement for orders in NYSE-listed securities. The move accompanied a similar offer from Knight for orders in Nasdaq securities. Madoff had offered price improvement on a best-efforts basis since the early ’90s, but did not guarantee it. BMIS soon followed Trimark, though, guaranteeing to price-improve the order if the spread was greater than a sixteenth.

The rush to offer price-improvement guarantees was not strictly a competitive matter. Market makers were then coming under pressure from the SEC to provide investors with “best execution.” The practice of simply matching the NBBO was being questioned.

Behind the SEC’s concern was an upcoming proposal from the NYSE to rescind its Rule 390, which prevented NYSE members from internalizing their orders in NYSE stocks. After first proposing the rule’s elimination more than 20 years ago, the SEC had finally prevailed over the exchange. Its removal would, in theory, create more competition for the NYSE specialist.

Despite its victory, the SEC still had concerns. If firms were permitted to internalize their flow, the market could fragment into potentially hundreds of competing marketplaces. That might eliminate the price competition that was the hallmark of the Big Board’s auction model.

In early 2000, concurrent with the New York putting its Rule 390 proposal out for comment, the SEC issued a concept release regarding fragmentation. It asked for public comment on six possible regulatory initiatives intended to mitigate any downside to an increase in internalization.

One of them-an anti-internalization, price-improvement rule-came from the New York Stock Exchange. It would require brokers to price-improve their orders or ship them to the market center that first quoted the market’s best price. In effect, such a rule could kill internalization and force market makers to ship most of their orders in NYSE-listed securities to the New York, as the exchange typically set the best price first.

Dealers opposed the New York’s suggestion, of course. If they were forced to route their hard-won order flow to other execution centers, they said, they wouldn’t compete as aggressively for those orders in the first place. “People want to be able to retain their order flow,” Madoff told Traders Magazine at the time. “And they should, providing that their customers get the best price available. Matching [the NBBO] should solve that.”

In the end, the SEC settled for the least drastic recommendation on its list: disclosure. It approved Rule 11Ac1-5, which required market centers to publish uniform execution-quality statistics. That way, their customers could compare one trading venue against another. From 2001, dealers would have to make available to their customers such data as effective spreads, execution speeds and levels of price improvement.

The SEC did not let the order-sending firms off the hook. It approved Rule 11Ac1-6, which required brokers to document which market centers they sent their orders to and in what quantities. Both rules applied only to orders of fewer than 10,000 shares.

Meanwhile, the New York’s proposal to eliminate Rule 390 was approved by the SEC, to no one’s surprise. It was the end of an era, but its absence left the future of stock trading an open question. Would the marketplace fragment into a collection of dark pools? Or would the status quo prevail?

The passing of Rule 390 had potentially devastating effects for Madoff. Many of his customers were brokerages with trading operations. They were now free to trade as principal against their NYSE flow. They might decide not to outsource that trading to Madoff.

In the end, however, the rescission of Rule 390 was a non-event. Business carried on as usual. The major wirehouses continued to send their retail orders to the New York. The regionals and the discounters stuck with their outsourcing arrangements. Madoff stayed in business.

The institution of Rule 11Ac1-5 was another matter. Despite being the least disruptive change of the six possibilities, Rule 11Ac1-5, or “Dash-5,” had a major impact on the business of filling small orders. Some older firms shut down their trading operations, as they were unable to beat their competitors’ numbers. Some new firms with highly automated trading operations entered the business.

For Madoff, initially, the Dash-5 stats were good news. His numbers outshone those of many of his peers. “We were number one in every category,” Bernie told Traders Magazine. “That’s the way we’ve always executed these trades. It was no surprise to us. Our execution quality is certainly better than the primary markets’, as well as that of our competitors. We’re thrilled with the stats. They confirm what we have always told our customers.”

Based on numbers coming out of Nasdaq and the NYSE at the time, Madoff’s comments about the primary market seemed to ring true. In April 2002, 10 months after the Dash 5 regime kicked in, the Nasdaq InterMarket, its venue for dealer trading of listed names, recorded an all-time-high market share.

Nasdaq now accounted for 11 percent of all trading in NYSE-listed shares, up from 8 percent in June 2001, when Rule 11Ac1-5 went into effect. During the same period, the New York’s market share dropped to 81 percent from 85 percent. When asked by Traders Magazine, the NYSE shrugged off the dip, attributing it to normal ebb and flow.

Mark Madoff, in charge of NYSE-listed trading at the time, had a different view. “The new rules have demonstrated that third-market players have done a better job than the primary markets,” he told Traders in 2002. “For the first time, you are able to quantifiably define best execution. Because of that, our volume has increased.”

Actually, the rise in 2002 was the first time in at least four years the third market had notched up any further gains in market share. Trading in the third had exploded in the aftermath of the Crash of ’87, but stalled 11 years later. In June 1998, Nasdaq’s share of the volume was 8 percent, no different than it was in June 2001. Its share of the trades was 11 percent.

Decimalization

With the rescission of NYSE Rule 390 seemingly a non-event, and the advent of the Dash-5 regime a shot in the arm for a stagnating third market, the early years of the new century looked good for Madoff from a regulatory standpoint. Any questions that his firm might not be offering its customers best execution were laid to rest by the statistics he published every month. Any concern that orders might stop coming in the front door were also relieved.

Actually, around this time, with decimalization just around the corner, it was the back door that was Madoff’s biggest worry. Once an order came in the front door, it often created a position that had to be unloaded into the marketplace through Madoff’s back door, or trading room. Madoff employed about 40 people in that trading room, a significant expense. With decimalization likely to crush spreads on the stocks Madoff traded by up to 84 percent, the costs associated with that trading room would suddenly loom much larger.

Decimalization hit in 2001, reducing the minimum trading increment from 6.25 cents to a penny, an 84 percent reduction. Firms knew it was coming, of course, and had made their plans. Still, it had a tremendous impact on every trading desk on Wall Street. BMIS’ desk was no exception.

As early as 1999, BMIS began preparing for the surge in orders it expected to accompany penny ticks by upgrading its automatic execution system. For this, BMIS turned to the former TCAM technologists who had built its original system back in the 1980s.

It was the trading operation, however, that would get the most drastic overhaul. Madoff, like most trading chiefs on Wall Street, set out to replace his human traders with robots, or algorithms.

Although known as a technology-savvy operator, Madoff still employed humans to make markets. Humans sat in front of quote montages and changed their prices in reaction to or ahead of changes in their inventories. The heart of market making was adjusting the firm’s prices, and at BMIS, as at most firms, humans still performed that function.

That was about to change.

Shortly after decimalization took effect, Madoff hired Josh Stampfli to automate the market-making operation. Stampfli, a former hedge fund trader, had been chief executive of Gale Technologies, a start-up birthed by brokerage A.B. Watley to commercialize a product called the Liquidity Engine. The technology had been used by Watley, an online brokerage, to automatically fill incoming orders. Gale was set up to sell the system to other brokers interested in internalization.

Gale, though, ran out of cash during the market downturn between 2000 and 2002. Stampfli was looking for his next assignment. Mark and Andy Madoff offered the trader/technologist a home. His job was to automate market making at BMIS.

“We determined the best thing for us to do was basically to take the human being out of the equation,” Bernie said at a forum on Wall Street held in New York last year. By automating the process, the trader added, a team of seven people was able to process the 300,000 trades per day that previously required 40 or 50. “This is what all market-making firms do today,” Madoff said. “That’s the way they operate.”

With fewer traders needed, BMIS’ employee roster began to shrink. From a high-water mark of 179 employees in January 2003, BMIS’ staff shrunk to 146 by January 2006.

New Ballgame

Despite the boost the SEC’s Dash-5 stats gave his business, Madoff’s euphoria over the quality of his numbers would be short-lived. The firm went into decline after 2002 as sophisticated new players entered the wholesaling business and NYSE members began to internalize more of their flow in the wake of Regulation NMS. Revenues from the market-making operation were $42 million in 2002. They fell to as low as $13 million in 2007, before rebounding to $32 million last year.

Competition from two newcomers from the hedge fund space-ATD and Citadel-played a big role in Madoff’s decline.

Automated Trading Desk, or ATD, now a part of Citigroup, had been making a quiet living using advanced trading algorithms to manage money for a small group of private investors. In 2002, it turned its attention to the market-making business and quickly started beating Madoff at his own game. ATD employed no traders, relying on computers to do all the work.

By 2005, ATD had grabbed a good chunk of the retail orders in NYSE stocks from TD Ameritrade, Piper Jaffray, Southwest Securities and Morgan Stanley. By 2008, it had 29 percent of the business, according to data compiled by Barclays Capital.

ATD was joined in 2005 by the broker-dealer unit of the giant hedge fund Citadel. Like ATD, it too employed sophisticated algorithmic trading strategies to both predict the direction of stock prices and make its markets. Citadel now commands about 30 percent of the market, according to Barclays.

The more traditional players, such as Knight and UBS, which entered the business through its purchase of Schwab Capital Markets, were determined to stay in the game. Both retooled their trading operations, replacing hundreds of traders with computers. Knight now controls a third of the business.

The customer was king. Prodded by the SEC, order senders started taking the Dash-5 reports seriously in the 2003-04 period, sources say. They were constantly comparing one wholesaler’s numbers against another. Janney Montgomery Scott was one Madoff customer to reduce the amount of listed flow it sent to the broker. “The rules started to change,” said Hughes, a former Janney executive. “We instituted regular and rigorous reviews, so we were constantly monitoring the execution data. That’s why ATD came along, There were times when ATD was much better than Madoff on a certain stock. So you’d send the order to ATD.”

The upshot was that Madoff saw its customer base dwindle to less than 100 from its high-water mark of 350 during the boom years of the 1990s. Its share of the wholesaling business was 19 percent before it shut its doors last year. According to published reports, the business accounted for no more than 10 percent of BMIS’ revenues in 2007.

Not all of the problem can be attributed to the entrance into the business of sharp-penciled hedge funds. Regulation NMS, the New York’s hybrid market and the NYSE’s decision to demutualize have all led to greater levels of internalization by NYSE members. It took five years, but the elimination of NYSE Rule 390 finally had its desired effect.

The Madoffs saw it coming as early as 2004. “Brokers are starting to look at [internalization],” Andy Madoff told Traders Magazine. “Reg NMS is a big deal. Once it is more defined, firms will make more of a move.” Citigroup is a prime example. In 2003, the giant retail broker was sending Madoff 14 percent of its small orders in NYSE-listed securities. At the end of last year, it sent them nothing, opting to internalize more than half of the flow.

In the end, Madoff’s wholesaling operation was undone by the very same forces that set the firm in motion back in the 1960s. Regulatory changes put Madoff on the map. Regulatory changes nearly drove him off of it.

Perhaps more than any brokerage on Wall Street, Bernie’s wholesaling operation was a shaped by the agenda in Washington. From Nasdaq to the National Market System to decimalization to Reg NMS, BMIS both influenced and was affected by all of the major regulatory mandates. It adapted. It thrived. It ultimately declined.

-Michael Scotti provided additional reporting for the story