ne of the things financial markets do really efficiently is to isolate whatever economics are in the system and to allocate them as assets and price risks.

That’s even true of trading economics. We’ve already seen how inverted venues are used to “buy” queue priority by those with urgency for a fill, as well as how algorithms seem to be increasingly deploying dark mid-point orders and odd lots to minimize costs. This effectively counteracts some of the inefficiencies of artificially wide spreads for high and low priced stocks.

Unfortunately, most of the market structure debates argue a classically oversimplified view of U.S. equity markets. A more complete view of U.S. market structure shows that the costs of markets are also pretty efficient at allocating resources and costs to participants. That is inclusive of (rather than despite) incentives to attract liquidity, tiers to offer economies of scale and cross subsidies on platforms with joint products—all of which are commonplace in the broader industry.

Even so, U.S. equity market is still the most transparent, cheapest and most liquid market in the world, and recent regulatory changes have only increased that transparency.

That’s partly because markets have solved for some of the more complex trading rent and revenue allocation decisions.

Who benefits from lit quotes?

Let’s start with trading and quotes.

Price discovery is important to all investors. The NBBO provides a benchmark for retail executions as well as a guardrail for dark pools. And yet few of those participants contribute to price formation. An economist would say the off exchange trades “free ride” off the quotes of others. But even that’s not really true.

One key reason for this, is that when Reg NMS was created, regulators confirmed that all investors should pay for NBBO data at the point of a trade, generating either “SIP revenues” or “top-of-book” revenue for the exchanges.

This means that although retail investors and dark pools might never trade on exchange, by buying the SIP or top-of-book data in aggregate, they do contribute revenues to exchanges who are providing good quotes.

Who pays for lit quotes?

Those same regulators decided that SIP revenues would be allocated to exchanges based on each exchanges contribution to price discovery and market share. It’s not enough to have high trading market share, half of the revenue allocation is for having stable quotes at the NBBO. Likewise, exchange top-of-book data in aggregate is only valuable if the exchange is generally at the NBBO.

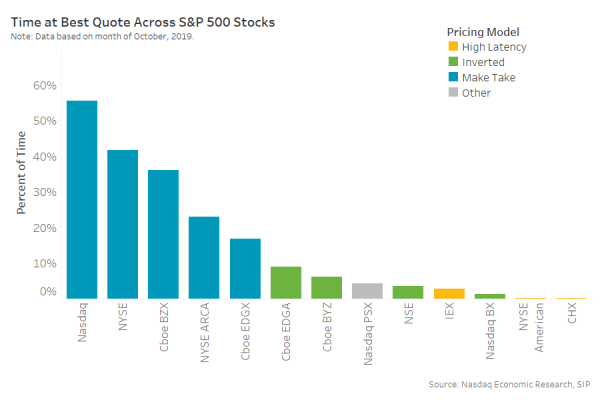

Our data has shown that only exchanges that offer incentives for liquidity provision have quality quotes (Chart 1). This can be done in a number of ways. Some venues offer queue priority for market makers, although it’s most common to offer financial incentives to anyone that provides lit quotes—the so called maker-taker model.

In contrast, we’ve seen recently how exchanges that don’t focus on the economics of lit market quality see spreads and liquidity can both be worse.

Chart 1: Data shows that maker taker venues are far better at providing price discovery than other venues

The market allocates the costs across the platform

A taker could say that they are paying for lit quotes, via their take fees. However that’s only partly true.

In fact an earlier analysis seems to indicate that although takers pay take fees, they also benefit from lower spreads and more liquidity at the touch, which reduces their taking costs. The fact that market forces are at work likely means the allocation of costs are a more efficient than it appears, even in our decimal trading world.

Most exchanges have also discovered that the best liquidity providers tend to do a lot more trading than average investors. Charging everyone an “equal” price to trade wouldn’t be fair to those liquidity providers. Offering decreasing marginal costs is not only standard across most industries, it also increases market quality for everyone.

In fact Nasdaq offers the best economics to market makers that contribute to smaller cap quotes and liquidity too. That might be a “cross-subsidy,” but it’s also a public good.

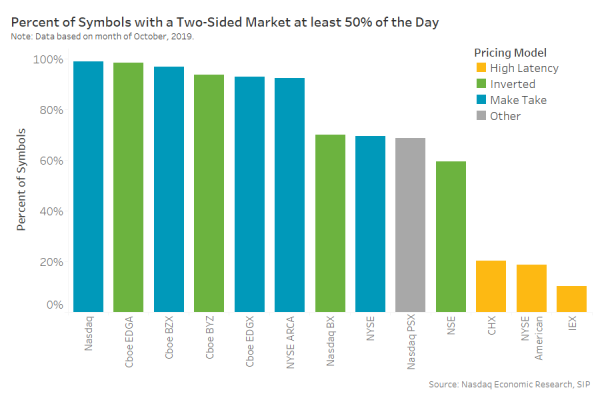

Chart 2: Two-sided market across exchanges

Importantly too, exchanges don’t keep all of the SIP revenues and take fees paid to them either.

Public data on exchange pricing shows that the best quote providers often earn higher rebates than the take fees they pay. Economically that results in SIP revenues and take fees being shared with those who contributed to the quotes, and in a ratio consistent with their contribution.

In addition, the U.S. market is so competitive that most TRF revenues are actually passed back to the off exchange venues that produced them. That means the wholesalers filling retail trades are actually receiving SIP revenues in response to their retail trades executed.

Don’t forget what’s important to issuers

Issuers are often forgotten in the market structure debate. But in my meetings with them, most expect their exchange to ensure that their stock trades well, so investors are confident in buying their stock. That’s another reason why it’s important for a listing-exchange-platform to focus trading economics on improving market quality.

But investors shouldn’t forget the value a listing brings to the industry too. Without public companies there would be no opportunities for investors to build wealth from equities, or tickers for traders and hedgers to trade.

Although investors might feel it’s unfair that market makers receive so many incentives, remember that investors benefit from the income and gains of long term investing, as well as the lower spread costs when trading.

Importantly, issuers also benefit from efficient markets. As we saw recently, even slight improvements in quotes can materially reduce WACC and boost valuations.

What about data revenues?

So what about proprietary data?

From an economic perspective, prices and trading are “joint products” of an exchange. One would not exist without the other.

What does this mean?

Consider how bond markets work. Without exchanges to produce data, few downstream data products exist. In fact, most investors aren’t even able to measure best execution.

But for equities, the existence of exchange data allows for many investors to compete with equal information and access to build profitable businesses. Whether that’s a trading strategy, a data terminal, a stock screener or a downstream application like TCA.

In fact a recent WFE paper “challenges the notion that (it’s fairer to) engineer any value transfer from those who create the product; to those in the financial markets who wish to exploit it for their own commercial ends.”

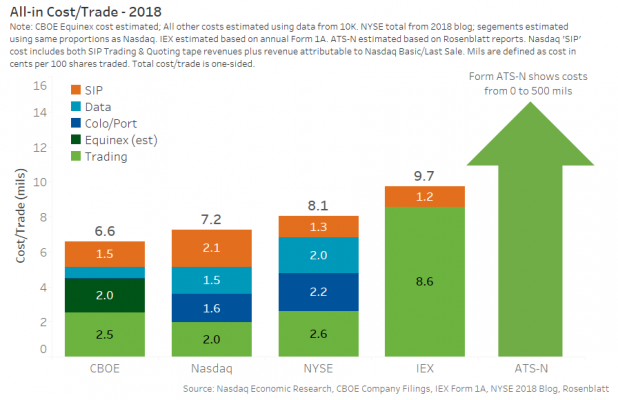

Logically, both trading and data have value to different parts of the industry, and in fact we see that different customers buy each. Economically, it makes sense to sell both. Interestingly, our data shows that exchanges who charge for both are actually cheaper than those who offer data free (Chart 2).

To an economist that’s not surprisingly, as free things result in inefficient allocation of resources, something IEX recently discovered.

Chart 3: Net costs of trading on most exchanges is small

Regulators have been critical of tiers and cross subsidies on exchanges. However the latest ATS-N disclosures (used for Chart 3) highlight just how commonplace they are. ATS charges are being reported as ranging from “free” to over 500mils, with one ATS even offering incentives. The move to commission free retail trading highlights similar platform economics in that side of the industry. Importantly, all three (ATSs, Retail and Exchanges) compete with each other for trading and liquidity.

Are direct feeds fair?

The “direct feed” debate is complicated by the fact that the SIP already exists.

However, it’s important to realize that something as simple and affordable as the SIP is perfectly adequate for retail. For a few reasons, the SIP is all they need:

- Retail rarely trades on exchange.

- Their trades are typically so small that they don’t trade with Level 2 or full depth data.

- Human reaction times are much slower than the SIPs (SIP processing time is around 300 times faster than the human eye can blink, even including geographic latency).

Arguably, SIPs also offer plenty of data for most eyeball traders (buy-side, Financial advisors, etc.) too, who aren’t building algos, but need to monitor market prices and volumes at human speed.

Who should pay for market depth data?

In contrast, professional investors, with much larger orders, often demand faster price feeds and much more information. Some say this should be added to the SIP, but ironically that would:

- Add to the costs of the SIP (and be borne by every investor whether they want it or not).

- Not remove geographic latency.

- Slow the SIP down even more (thanks to all the additional processing required).

- Add more data to the government mandated monopoly thus stifling innovation.

A better solution for all participants is to provide choice so that professional investors buy the additional technology and data they need separately, as they currently do. In fact our data shows that not all professional investors have the same appetite for direct feeds data and colocation capacity. The user pays solution results in less free riding or cross subsidies.

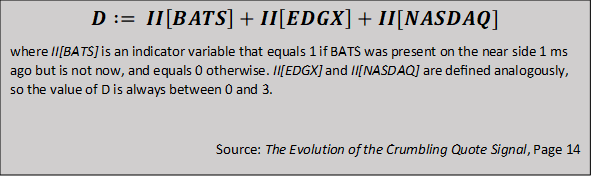

There is perhaps no better example of this in the current debate than IEX’s DPEG formula, especially because of their position on so many of these issues.

Not surprisingly, their regression shows that maker-taker exchanges have the most informed prices, despite the fact that they have openly criticized the maker taker model.

They then use those direct feed prices from competitors, combined with a speed bump on incoming take orders, to allow their calculator to fade resting orders before the takers arrive at their venue.

Chart 4: IEX’s DPEG product relies on depth data from maker taker exchanges, because their regression models show that’s the best way to get price discovery information

We estimate that the majority of IEX’s revenues require depth data from other exchanges. On that basis it’s not surprising they’d prefer all that data to be free, but according to their Form 1, IEX earns more than $70 million from matching and routing.

Getting inputs for their main product, from all of their competitors, for free, hardly seems fair.

We all benefit from centralized markets, let’s understand all the economics before changing specific policy

Considering each cost in our market in isolation misses the big picture. Most businesses in finance are platform businesses. In the case of listing exchanges, that platform brings many benefits: bringing companies to investors, creating transparent prices that are available to all and centralized liquidity for risk management and hedging. Those features makes the whole industry more efficient and investors are better off.

But competitive market forces allocate the complex economics of trading, data, colocation and listing among participants, resulting in economics being shared between participants.

The main argument seems to be whether those that create the most value extract enough of the rents.