This week was historic. We hit the new 7% market wide circuit breaker (MWCB) for the first time ever on Monday, March 9, 2020. Of course, Thursday morning we hit it again.

Importantly, this was not the first time the market has fallen over 7%. Over time, guardrails have been added to the market and progressively changed. Back in 1987, the market fell over 20% in one day. By the time of the Credit Crisis, the first MWCB was set at 10%. After the Flash Crash of May 2010, that was reduced to the 7% level we see now back in May 2012.

It’s too early to analyze the data on how today’s MWCB performed, but let’s look at what the data show about how the market performed on Monday under such stress.

What did (and didn’t) happened on Monday morning?

There were a few similarities to Aug 24, 2015. It was a Monday, a combination of negative weekend data had pre-market futures down 5% (their pre-market limit), and there were expectations that we would likely see the market down 7% early in the morning.

But the data show the market performed much better this time around. Why?

Back in Aug 24, 2015 the S&P500 futures fell through 7% but the market didn’t halt. That turned out to be because the S&P index did not show the market down as much. That created confusion whether futures or stock markets were right. That in turn made it hard to hedge stocks or price many ETFs.

It turned out the reason the MWCB didn’t trigger for stocks was the S&P500 index was waiting for the NYSE to manually open their stocks. Until stocks opened the index saw the returns on some of the largest U.S. stocks as unchanged. However, NYSE delayed the opens of stocks up because of the volatility. That in turn caused more selling to flow into equities that were open, causing them to sell off more, and also disrupted normal cross-market statistical arbitrage liquidity-providing strategies.

That ultimately caused a number of single-stock circuit breakers to trigger. That compounded liquidity, hedging and valuation problems, which was especially bad for pricing and trading in ETFs.

As a result of the discontinuous hedging and liquidity, ETFs were arguably the most affected stocks of Aug 24, 2015.

This past Monday differed from 2015.

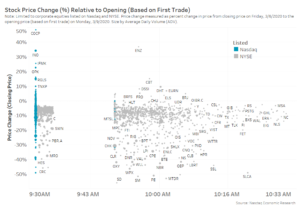

Chart 1: Initial open time for all stocks on Monday, March 9, 2020

Since 2015, a number of changes have been made to market rules. One important change was S&P index moving to use consolidated quote data to calculate the important MWCB levels so that late NYSE opens wouldn’t understate the market levels used for the MWCB.

That proved to be important on this past Monday’s open, as it allowed trades on other exchanges to correctly price the whole market and halt stocks at roughly the same times as futures. Data (in Chart 1) shows that NYSE stocks were slow to open, with around 58% of all NYSE tickers trading for the first time on NYSE after the reopen at 9.49 a.m.

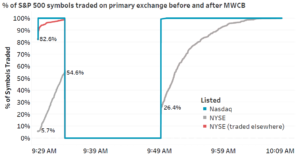

Even for the liquid S&P500 stocks, we estimate only 55% were officially opened by the time of the MWCB (Chart 2). However, we saw trades in almost 100% of NYSE-listed S&P500 tickers, which allowed the S&P500 index to price close to correctly and stop the market at the correct time.

Chart 2: S&P used the SIP to compute the MWCB, making late opens less of a problem

How did the reopens go?

From a market-wide perspective, both the halt and the re-open worked well.

On reopen, the broad market saw support from buyers, with the S&P500 index recovering around 1% by noon on March 9.

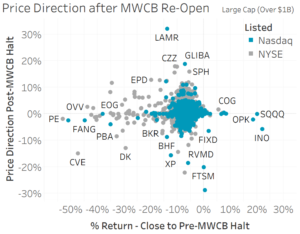

From an individual stock perspective, stock reopens weren’t bad either. Data show there were a mix of net buyers and net sellers across tickers. In Chart 3 the vertical scatter of the data highlights how stocks rallied and fell on reopen. Despite the continued uncertainty, our estimates show 94.3% of Nasdaq-listed and 92.3% of NYSE-listed large-cap stocks moved less than 5% up or down from their previous last trade on the reopens.

Chart 3: Re-open price moves, after the MWCB stopped trading, saw roughly equal gains and losses for stocks

Many single stock guardrails were also hit

In addition to the MWCB that protects the broad market from selloffs, there are also stock specific protections known as limit-up-limit-down (LULD).

At a basic level, LULD sets guardrails to stop quotes increasing or declining too fast. The bands vary by stocks and time of day, but for large-cap stocks they are around 5% up and down from the recent last prices for most of the day.

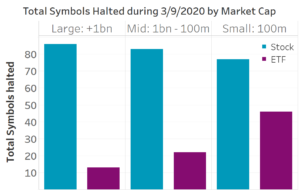

Because of the velocity of trading on March 9, many LULD levels were also hit. In fact we calculate there were 518 LULDs on March 9, affecting 327 different tickers. That’s well above the longer run average of 11 per day. Of those, 112 were in ETFs. Only 3% of all ETF tickers saw LULD halts, while a higher 5% of stocks saw LULDs. That’s in contrast to Aug 24, 2015, when ETFs were the majority of single stock halts.

Chart 4: Single stock halts were more concentrated in stock trading than ETFs, in contrast to Aug 24

As the day progressed, things returned to “normal”

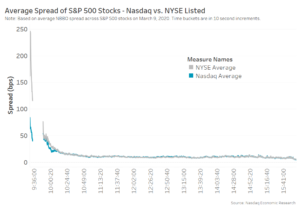

Although the Monday sell-off ranks as one of the largest single day drops in history (#19 actually), trading for the rest of the day was relatively normal. Even spreads compressed to near normal levels averaging 11 basis points (bps) for S&P500 stocks in the afternoon.

Chart 5: After re-opening, trading became reasonably orderly and spreads compressed

What can we learn?

The reasons for the sell-off were real. Coronavirus is looking like a real challenge to global growth and public health. A prolonged pandemic will affect goods and services companies, some significantly. A sharp but quick pandemic will stress the health system and likely have higher casualties.

Pricing in the economics of that is what markets do well. We are still a long way from the 60% drop in stock valuations seen in the Credit Crisis, but this may turn out to have far less impact on the economy too.

Despite all that, Monday was a test of many new processes designed to help the market avoid negative feedback loops leading to unnecessary volatility. On that measure, the changes made have proven overwhelmingly good.