TECH TUESDAY is a weekly content series covering all aspects of capital markets technology. TECH TUESDAY is produced in collaboration with Nasdaq.

As we recently mentioned, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) published a lot of rules last year. Four proposed rules released right at the end of the year are designed to change how markets work and seem to have a common thread, which is to change how retail trading works in the U.S.

There is a lot to digest (1,656 pages of rules for a start!), and that’s before we look at what the research around all of these topics shows.

We plan to file a comment letter (which are due March 31, by the way) where we can state our positions and potentially suggest some improvements to the proposals.

But for today, we summarize these new proposed rules, with some visuals of how the rules work and data on what stocks could be impacted to help our readers understand the new rules better.

What do the four new rules cover?

Retail trading increased significantly during Covid and remains active. On top of that, MEME stock trading in 2021 increased the SEC’s focus on retail market structure and trading. Given that, it’s probably not that surprising that the SEC’s proposed changes mostly affect rules affecting how the underlying plumbing of retail executions works. Although, as we show, other changes could impact how stocks trade more generally, too.

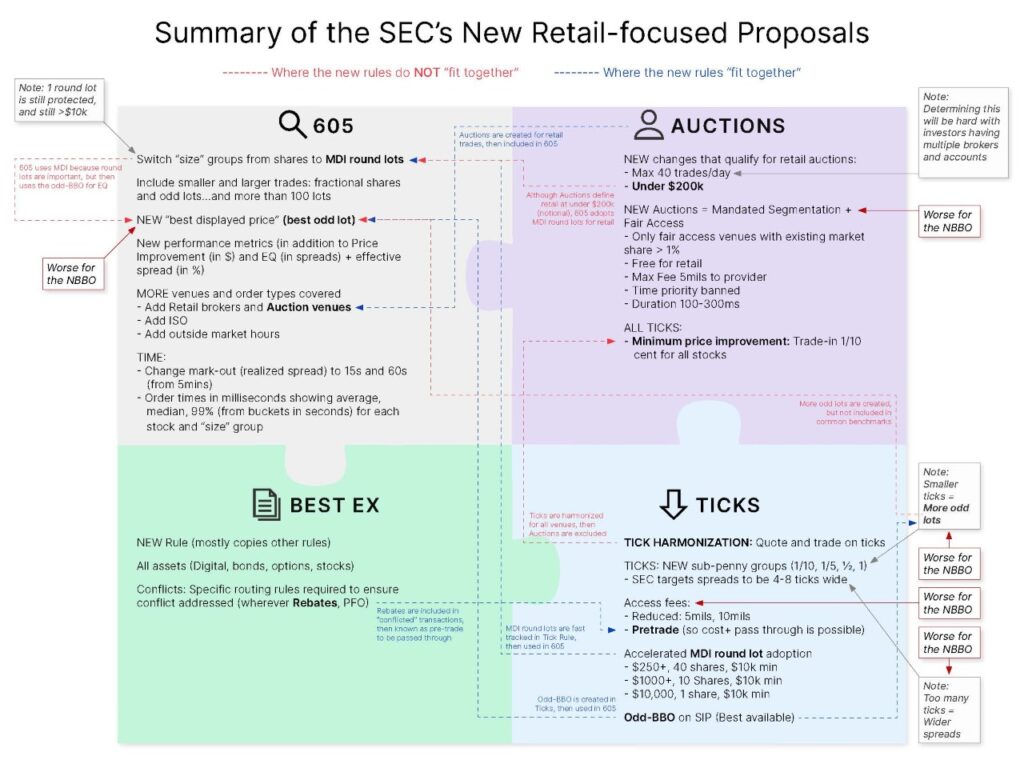

We show the four new SEC proposed rules in the infographic in Chart 1 below. In essence, they cover:

- New Retail Auctions or the “order competition rule”: requires brokers to submit orders to new fair access auctions where anyone can compete to trade with incoming marketable (spread crossing) retail orders. It also includes a minimum 0.1 cent tick for retail.

- Enhanced 605: Computes execution quality for retail orders and will expand to cover auctions and retail brokers, stop and outside market hours orders and additional order sizes like fractional, odd lot and even larger than 100 lots.

- Best Ex Rule: Similar to rules that FINRA and MSRB have, this requires agency brokers to have written policies and procedures to assess venue execution performance and more robust policies for routing retail orders to venues from which brokers receive PFOF or rebates, or to affiliates executing with their proprietary books. And the new proposed rule would apply a best execution duty to brokers in all securities, including bonds, stocks, options and crypto.

- Much smaller, harmonized tick increments, updated access fees, odd lots on SIP, redefined round lots.

Chart 1: A summary of the new proposed rules and how they do and don’t work together

There are places where the new proposed rules are designed to fit together (blue connecting lines in Chart 1):

- Portions of the NMS-II MDI dynamic round lots that created dynamic round lots are accelerated in the new Tick Rule – and then used in the new Rule 605.

- The new Tick Rule also creates a new “odd-BBO” on the SIP (a “best displayed price”) – and that is also then used in the new Rule 605.

- Having created the new Auctions Rule – the new Rule 605 requires these new Auctions to produce execution quality reports.

- The new Best Ex Rule talks a lot about supposed routing conflicts and asserts that rebates and PFOF present conflicts for agency routing to overcome, but the new Tick Rule requires that rebates be known ahead of time, allowing brokers to pass them on to investors. Based on this research paper, a passive investor would then be indifferent to where they route.

However, there are other places where they don’t (red connecting lines in Chart 1):

- The new Auctions Rule creates a new definition of retail, below a $200,000 trade, which is consistent with block size for institutions. But in adopting MDI round lots, the new Rule 605 will blend orders on either side of the Auction size cap (under $200,000) into most of the new size buckets (see Chart 5).

- The SEC’s argument for using MDI round lots in the new Rule 605 was so that all “protected” trades would be in the same buckets, with odd lot execution quality shown separately – however, the new Rule 605 would measure executions against the best displayed price (odd-BBO) anyway.

- The new Tick Rule harmonizes ticks for all venues, requiring all to quote and trade on the new ticks. But then the new Auctions Rule sets all retail executions at 1/10th of the tick size regardless of the tick of the underlying stock.

Today we look through these new proposed rules, what is proposed and how it all might work.

Adding auctions to create order-by-order competition

The new retail auctions, or “order competition” rule, does a number of things:

First, it redefines retail as:

- As an order worth less than $200,000;

- That originates from a natural person or group of related persons; and

- Who trades less than 40 times a day on average during each of the past six months.

The rule then mandates that almost all retail spread crossing orders are sent to an auction and prescribes how these auctions will work (Table 1).

Importantly, the rules state the auction message will include side, size and retail broker name – so each auction will be unique. This will mean there could be multiple auctions in the same symbol at once.

However, auctions aren’t mandatory for:

- Passive (near touch side) limit orders

- Orders worth $200,000 or more

- A wholesaler who can fill orders equal to or better than midpoint

- Or for fractional share size orders (i.e., orders that are for less than one share of stock)

Table 1: Auctions are asymmetric by design: fair access for market makers, segmented for retail

One thing that makes these new retail auctions different from the retail programs that operate on exchanges now is the attribution by retail brokers.

Attribution is important, as each retail broker has a different mix of customers, some of whom are more profitable to trade against than others. That, in turn, allows market makers to offer better prices to “less informed” customers and still make some profit from spread capture.

In fact, BestEx research recently theorized that because of attribution now, the “right” BBO benchmark for each retail broker should be different because the effective spreads that are profitable for each group would vary. More recently, an academic study proved that to be true – when they received consistently different fill prices on the exact same order, sent at the exact same time, from different retail broker accounts (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Price Improvement now mostly depends on the retail broker sending the order

The other feature of the proposed fair access auctions is that they aim to help mutual funds trade against retail flow more easily while still using their favorite algo brokers.

An interesting question is how much might retail and mutual funds actually trade with each other. We know from the data that some retail investors like to trade more thinly traded stocks than institutional investors typically do. Although based on our data, we estimate around 61% of all retail value traded, adding up to $21 billion each day, is in institutional benchmark stocks (Russell 3000 and S&P500).

Chart 3: Retail trade a wider range of stocks than institutional investors

The SEC argues this rule has cost savings for retail of around $2 billion each year, although Bloomberg thinks that’s too high, with their estimated retail savings closer to $800 million each year. In addition, BestEx research estimates institutional investors/mutual funds would save around $1.8 billion each year.

Modernizing 605 to keep retail routing (and auctions) accountable

Of course, having created retail auctions to change how retail orders are executed, it naturally follows that the 605 reports, which report on retail execution quality, would also be enhanced.

Rule 605 is designed to track where a customer execution occurred compared to the NBBO at the time the order arrived at the market. Doing that helps highlight fills at bad prices and shows how often customers’ orders execute better than, as well as worse than, NBBO.

Some of the metrics the new 605 will calculate are shown in Chart 4, and include effective spreads (costs from midpoint in cents and percent) and price improvement versus the NBBO and the odd-BBO (in cents). The “EQ ratio” will also be computed for each order, showing the effective spread savings from the NBBO midpoint in terms of the NBBO spread, where 100 is paying the full spread, and 0 is paying midpoint.

These metrics are calculated separately for different levels of order aggression – from market orders to limit orders. One change is to trigger the “execution speed” clock on “out-of-the-money” bids once they reach the NBBO rather than when they are submitted by the customer, as they are not executable until they are at the NBBO.

Another new metric would score size improvement if the order size was larger than the NBBO when it was filled.

Chart 4: Visualizing a lot of the different things 605 calculates

Given 605 is designed to track “covered” (mostly retail) orders, which tend to be mostly very small orders, we have talked before about some of the problems with how 605 works. As the table below shows, the new rule addresses many of them:

Table 2: The new 605 rule addresses a number of common complaints

As we explain more below, one thing the Tick Rule does is fast-track the adoption of the MDI dynamic round lots. Then, the 605 Rule adopts these new round lots for its buckets. Although that reduces some of the very large trades that used to count for EQ against much smaller trades, it still creates the zig-zag shape for notional size included in each bucket (Chart 5), where clearly different-sized trades are still included in the same bucket, as stock prices rise.

The SEC thought about whether it would work better in dollars, and even cited an analysis of ours to that effect, but it decided that shares make more sense because everything in the blue (and higher) buckets are protected quote size. This results in higher-value orders that qualify for retail auctions being mixed with orders that don’t (which will affect blended reports at the retail broker level).

Moreover, even though MDI dynamic round lots were meant to fix the odd lot problem, these rules acknowledge that odd lot problems still exist:

- The Tick Rule creates an odd-BBO, and then the 605 Rule uses it to compute new performance metrics.

- The 605 Rule also adds buckets for odd lot-sized orders and fractional shares (as well as a bucket for even larger orders than before).

Chart 5: Using the new MDI round lots, the share buckets capture trades that are more similar sized

Some might say that the 605 reports won’t look that different. The table below shows what a detailed 605 report looks like for just one ticker. We have color-coded it to show exactly what is unchanged (grey heading), changing (orange heading), deleted (pink heading), and what is new (green heading). We see that many columns and calculations are changing quite significantly.

Chart 6: Comparing the old and new detailed 605 reports

For each ticker, the 605 report is currently 20 columns wide by 20 rows deep, adding to 400 data points. New reports will be 37 columns wide by 42 rows deep, adding to 1,554 data points per stock.

Multiply the grid above by around 10,000 NMS stocks, and you start to see why the SEC wants these reports to be machine-readable while adding a summary-level report for humans.

We summarize the other key changes to the SEC’s new 605 Rule in the table below.

Table 3: Comparing the old and new detailed 605 reports

A new SEC Best-Ex Rule

In addition to creating retail auctions, smaller ticks, and a new broader execution quality report, the SEC decided it made sense to add an actual Best-Ex standard to police it all.

At its surface, it simply provides for the familiar requirements that broker-dealers must establish, maintain, and enforce written policies and review the execution quality of their customer transactions at least quarterly.

But the scope of the proposed rule is more comprehensive than the existing FINRA and MSRB Best Ex Rules, as it extends the duty to broker-dealers in bonds, options and crypto.

A portion of the proposed rule also explicitly requires more robust policies and procedures for so-called “conflicted transactions.” Conflicted transactions involve brokers routing customer orders (retail and mutual funds) to an affiliate of the broker for execution, or to a venue where the broker receives some sort of payment in return for doing so, such as PFOF or rebates for providing the venue with liquidity.

The focus on payments included in conflicted transactions, and the discussion in the rule about expected fill prices, seems to say that “all-in-costs” matter, which might also make it harder to “bundle” costs and charge customers an “all-inclusive-commission,” even if that commission is zero.

It’s possible this rule impacts dark pools, according to an academic study that found that brokers routing to their own dark pool increased opportunity costs for algo trades.

However, as we’ve said before, rebates are very different from other routing incentives. By being available to all and paid on lit quotes that lead to traders, they directly contribute to a tighter NBBO. That, in turn, creates “positive externalities” for the market – saving even those who trade off-exchange from crossing wider spreads, improving arbitrage and market efficiency, and reducing costs of capital for companies.

The data clearly shows that markets offering liquidity providers a rebate have more competitive quotes, which we have found is especially important for thinly traded stocks.

Chart 7: Time with a two-sided quote at the NBBO across all NMS Stocks

Interestingly, the new Tick Rule requires that access fees and rebates are to be known at the time of the trade – which would allow them to be passed through to investors. Tied with an academic study that says “net of fees and rebates, trading costs are statistically indistinguishable between maker-taker and inverted exchanges” – this suggests that a pass-through would eliminate the broker conflict with respect to exchange fees and rebates.

This gets us to the fourth rule….

Tackling the tick-constrained problem

We have written at length about how having the wrong tick makes a stock’s spread wider and increases the cost of capital for companies (see here, here, here and here). As part of that, we have argued that around 600 corporate stocks are affected by the tick-constrained stock problem. Many others in the industry would agree, including MEMX, Citadel Securities, XTX, Cboe and Blackrock.

However, there are also many that would argue that depth and odd lots are also important problems to solve, especially for institutional investors.

Table 4: What the new Tick Rule changes

The new Tick Rule tackles just the tick-constrained problem. It proposes much smaller ticks for almost all stocks, although different ticks than those proposed in the Auction Rule. It also creates much lower rebates for all stocks.

Also important for investors to understand is how the new tick buckets force almost all stocks to trade at least 4-8 ticks wide (by design, based on how stocks are selected for tick buckets):

- Any stock trading less than 4 cents wide now will go into the ½ cent tick bucket, giving it a spread up to 8 ticks wide (8 x ½ cent tick ticks = 4 cents, Chart 8).

- If tighter spreads result, and that stock’s actual spread improves to 1.6 cents (~3 x ½ cent tick) wide, it is promoted to the next bucket, resetting it to 8 ticks wide (8 x 1/5th tick = 1.6 cent spread)

Chart 8: New Tick Rules ensure that most stocks will have 4-8 tick spreads

That creates a lot of stocks with a lot of ticks. By the SEC’s estimates, over 80% of all shares traded, affecting 4,355 stocks, will trade in ticks less than 1 cent in the future.

We have also seen that at that level, the rate of pennying and excess message traffic could be a problem for mutual funds and market makers. Other research suggests having too many ticks actually widens spreads.

That result would also be the opposite of the results of our prior research on minimizing trading costs, where we found that there were far more stocks that would benefit from larger ticks than needed more ticks.

Additionally, recent research done by us and academics and other regulators indicates a stock has optimal trading with a 2-3 tick spread. Importantly, these new rules make it hard for any stock to trade 2-3 ticks wide, as a stock trading 2-3 cents wide now (at its perfect tick and likely optimal spread) will be placed in a ½ cent tick group (yellow group), creating a 4-6 tick spread. Splitting ticks that much may cause spreads to drift wider or see less depth. Consequently, this aspect of the proposal seems to have the potential to increase costs and harm market quality. In fact, looking at effective spreads (which include sub-penny and mid-point trades (Chart 10), we estimate just over 2000 stocks and ETFs trade with effective spreads 1.1 cents or less.

Using effective spreads, which include sub-penny and midpoint trades happening now, we can better see where stocks seem to naturally want to trade (Chart 9). There is a wide range of effective spreads that stocks trade at now, with only the first 6 bars being tick constrained. But under the proposal, it appears that the cutoffs for promotion happen well before stocks in each group reach tick-constrained levels (Chart 8). Consequently, we estimate:

- Around 5,700 stocks will trade in sub-penny tick groups (pink, blue and yellow tick groups).

- Over 1,000 stocks fall in the 1/10th tick group (pink) despite most having an effective spread of around 7/10th cent now.

- Over 4,000 stocks that currently trade more than 5 cents wide won’t see a corresponding correction to their own tick, despite many having high prices that create ticks well under 1 basis point wide, increasing odd lot problems, even under MDI round lot rules.

Note that we show ETFs as paler color bars in the chart below, showing that, despite having tighter spreads than similarly liquid stocks, many ETFs are also not tick-constrained.

Chart 9: What tick we expect each stock will trade based on effective spreads now

Of course, these smaller tick sizes, with existing access fees at 30 mils, would lead to economically locked or crossed markets even with an NBBO spread on the screen (as 30 mils are more than the 1/5th and 1/10th cent ticks).

Consequently, the SEC tackled access fees at the same time, reducing access fees to a flat 10 mil access fee cap across all stocks (except the 1/10th cent tick group, where it would again cause locked markets, which will be capped at 1/20th cent, or 5 mils). That seems to create:

- A complicated access fee sheet (see Chart 10 and table above).

- Much less meaningful NBBO setting incentives for all stocks, but especially for stocks that trade with much wider spreads (grey and pale yellow dots in the chart below).

In Chart 10 below, we show how ticks (dark dots) and access fees (light dots) work now in basis points (left chart) and would work in the new regime with the tick groups from Chart 9 (right chart, same tick group colors).

Interestingly, with the market-derived tick groups, most large-cap stocks (darker + large dots below) will see ticks less than 1 basis point, with many close to a 0.1 basis-point tick (right chart).

The right chart also highlights how the 10 mil fixed rebate for most stocks (faded colors) provides much less economic support, especially for wider spread and high-priced stocks (black dots), relative to their (wider) ticks, before accounting for how many ticks wide those stocks trade (Chart 10). At closer to 1/100th basis point (grey dots), rebates will become economically meaningless likely leading to wider NBBO.

Chart 10: Access fees in basis points for each stock

Although the SEC’s market-driven bucket approach to tick groups might look complicated, we found it worked better than creating tick groups based on price, as other countries do. That’s because it stops stocks like SPY, QQQ and MSFT from being forced to trade in a wider tick group.

What does this do for the NBBO

Given the SEC’s comments before the proposals were published about the importance of a strong NBBO to protect investors, it is somewhat surprising (and at times counterintuitive) that the changes appear unlikely to tighten list spreads, and on balance, we should expect the NBBO to widen.

Table 5: Incentives affect quote quality

What does this all mean?

So far, we’ve digested the proposals 1,656 pages into around 4,500 words.

We’ll do our best over the next few weeks to complement this by highlighting some of the research around changes like these, to help you all form your own data-driven views on how these might affect stocks for better or worse.

We start with a Nasdaq-hosted webinar on Feb. 16, 2023. If you want to sign up for that, click here.

Phil Mackintosh is Chief Economist at Nasdaq.