By Joshua Ray, Rahman Ravelli

Introduction

On September 29, 2020, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) announced a record-setting $920 million settlement with JP Morgan for alleged spoofing in U.S. precious metals and Treasury futures markets. That same day, it filed an anti-spoofing enforcement action against decidedly smaller targets: Roman Banoczay, Jr. and Sr., a father-son trading duo based in Bratislava, Slovakia.[1] While the JP Morgan settlement shows the continued reluctance of large financial institutions to challenge spoofing allegations in court, the Banoczays and other small-scale traders have significantly greater incentives to put up a fight.

For one, the action against the Banoczays seeks a broad injunction that would permanently preclude them (and anyone working for them) from ever again trading futures on U.S. exchanges.[2] Thus, if the Banoczays wish to continue participating in American futures markets, simply accepting the allegations or letting the case lapse into a default judgment is not a viable option.

Second, the CFTC is seeking a large financial penalty in addition to the injunction. Whereas the penalty against JP Morgan will hardly put a dent in its overall revenue, a million+ dollar hit against a small firm like Bazur will be crippling, if not fatal. And further, there is no guarantee that a financial resolution with the CFTC will be the end the matter (as Michael Coscia discovered in 2014 when he was indicted on spoofing charges after settling with the CFTC in connection with the same conduct a year earlier).[3]

Third, the Banoczays can confront the CFTC’s case without having to travel to the U.S. In contrast to criminal spoofing cases, which generally require a defendant to physically submit to U.S. jurisdiction before mounting a defense,[4] civil actions are much more easily opposed while the defendants remain in the (relative) safety of their home countries.

A Defense Blueprint

The cost/benefit analysis of settling spoofing charges for individuals is therefore clearly different from that of a big bank. Since the reasons such individuals might choose to contest the CFTC’s allegations seem clear, the next consideration is what defense strategy is most likely to succeed. As in most civil cases, such a strategy should generally begin with a carefully crafted motion to dismiss. But defendants in spoofing cases have been, to date, uniformly unsuccessful in dismissing the allegations against them.[5]

So how might the Banoczays’ succeed where others failed? One approach could be attacking the Commodity Exchange Act’s anti-spoofing provision (ASP)—which prohibits “bidding or offering with the intent to cancel the bid or offer before execution”—as impermissibly vague under the U.S. Constitution.

Concededly, this tactic has been tried before. Just last May, for example, Judge Lee of the federal court in Chicago denied a motion to dismiss on vagueness grounds filed by two former traders in United States v. Bases.[6] Judge Lee’s reasoning was driven by the Seventh Circuit’s decision in the 2017 Coscia case.[7] There, the court highlighted the importance of the ASP’s specific intent requirement: “The text of the [ASP] requires that an individual place orders with the ‘intent to cancel the bid or offer before execution.’ This phrase imposes clear restrictions on whom a prosecutor can charge with spoofing; prosecutors can charge only a person whom they believe a jury will find possessed the requisite specific intent to cancel orders at the time they were placed.”[8]

While the Coscia decision remains good law, the fact pattern it analyzed was unique. Unlike the Banoczays and the traders in Bases—who placed their orders manually—Coscia employed a computer trading algorithm. Coscia’s use of an algorithm, which could place and cancel orders in under 5 milliseconds, was critically important to the Seventh Circuit’s determination that the ASP was constitutional: “[Coscia] commissioned a program designed to pump or deflate the market through the use of large orders that were specifically designed to be cancelled if they ever risked actually being filled. . . . [This] clearly indicate[s] an intent to cancel.”[9]

But the same cannot be said of non-algorithmic traders. As such, the ASP cannot constitutionally be applied to relatively slow, manual trading strategies.

The ASP’s Intent Element Does Not Limit Who Can Be Charged With Spoofing

Since the ASP is concerned with cancellations, it targets only “resting” limit orders that do not aggress across the order book’s bid/ask spread.[10] But since resting orders make up the majority of orders entered, the critical question becomes: what specific type of resting order does the ASP purport to criminalize?

On its face, the ASP provides a seemingly straightforward answer: it prohibits resting orders that are entered with an intent to cancel them “before execution.”[11] But when this language is applied to manual traders, what exactly it prohibits is far from clear.

To begin with, an order cannot be cancelled after execution. Rather, once an order executes, it is instantly removed from the order book and becomes an executed trade.[12] While trades can be unwound in certain limited situations, it is impossible for an order to be cancelled after it is filled. To use a simple analogy, a marriage proposal cannot be retracted after the wedding—it the couple can get divorced, but once the marriage occurs, there is no longer any proposal to “cancel.”

The ASP’s use of the phrase “before execution” is therefore meaningless. Since an order cannot, under any circumstances, be cancelled after it executes, prohibiting orders placed with an intent to cancel “before execution” is the same as a ban on orders placed with an “intent to cancel,” full stop.

To return to the same analogy, one could imagine a statute criminalizing “making a marriage proposal with the intent to retract it.” Adding the phrase “before marriage” to this statute would have no impact on the types of proposals it makes illegal. Rather, both before and after the addition, the statute criminalizes the exact same thing: making a proposal with the intent to retract it. In the same way, the phrase “before execution” can be removed from the ASP without affecting the statute’s meaning.

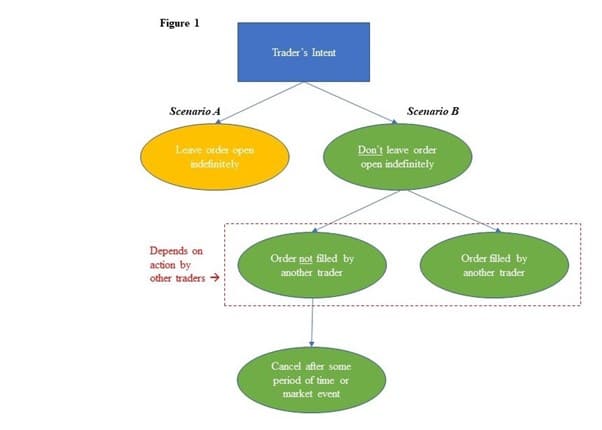

This is important because every resting order must necessarily be entered with an intent to cancel it if it is not filled by another trader. To see why, imagine being a trader about to place a resting order. With respect to how long you intend to leave it open for, there are only two possibilities: either (A) you intend to leave it open indefinitely or (B) you don’t. But Scenario A never happens, since futures traders operate in short timeframes that at the longest extend to the end of the trading day. This means that every resting order must fall into Scenario B (as seen in Figure 1).

Following this logic, only one of two things can happen to a resting order that is not intended to be left open indefinitely: (1) it is filled by another trader, or (2) it is cancelled at some point.

Yet what happens to a manually placed resting order is not fully within the control of the trader who placed it. To be sure, a resting order placed close to the top of the order book and/or left open for a long time stands a higher chance of being filled than one placed further away and/or kept open briefly (all else being equal). But in either case, the trader cannot be certain about what will happen to it.

This is not necessarily true of traders who employ algorithms, however. Because they can pre-program their orders to cancel before any counterparty has a realistic chance of filling them, such traders can ensure that their “spoof” orders are effectively un-fillable.[13] Insofar as algorithmic traders are concerned, therefore, it arguably does make conceptual sense to conclude that their orders were placed with the “intent to cancel” because they can effectively guarantee that result.

In contrast, a manual trader’s intent (the blue box in Figure 1) when placing an order must be to cancel only if it not filled by another trader. There is no other possibility.

Judge Lee’s Flawed Opinion

This essential point was missed by Judge Lee. He concluded that the manual orders described in the indictment were placed “with the intent to not fill them—that is, with no ‘willingness to trade.”[14] To support this conclusion, Judge Lee cited the Coscia decision: “The fundamental difference is that legal trades are cancelled only following a condition subsequent to placing the order, whereas orders placed in a spoofing scheme are never intended to be filled at all.”[15]

But this ignores the reality that all manual cancellations must follow “a condition subsequent to placing the order”—specifically, inaction on the part of other market participants to fill it. In other words, the absence of a market reaction to an order is in itself “a condition subsequent” upon which a cancellation can (and must) depend.

Since the fate of a manual resting order turns on action by other traders, Judge Lee’s contention that the alleged spoof orders were not “intended to be filled” makes no sense—a manual trader may intend to cancel an unfilled order following a relatively short period of time or upon an event that is likely to occur, but whether the order executes is fundamentally beyond her control.

To use another analogy, a manual trader placing a resting order is like a fisherman dropping a hook in the water. Regardless of whether she intends to catch a fish or not, she cannot manufacture either result. She can leave the hook in for longer or shorter time periods, but whether a fish takes the bait is ultimately up to the fish. So unless she is willing to wait forever to get a bite, she must intend to wind up the reel at some point.

In the same way, unless a trader is willing to leave a resting order open indefinitely, there will always be an intention to cancel in the trader’s mind at the time the order is placed.

Unconstitutional Vagueness

The reason this makes the ASP unconstitutionally vague as applied to manual traders is that neither the statute itself nor the CFTC’s interpretative guidance[16] provide any delineation between lawful and unlawful intentions to cancel.

With respect to the duration an order is intended to be left open, for example, the ASP fails to give traders any indication how long they must intend to leave it open for so as to not break the law. For instance, if a trader places an order with the intent to cancel it if it remains unfilled after five minutes, has she “spoofed”? What about 10 seconds? Or 1? There is simply no way for her to know.

Indeed, the arbitrary approach taken by regulators to spoofing cases is clearly seen when the allegations against Coscia are compared with those made against the Banoczays. As to Coscia, prosecutors used evidence that his “spoofs” were left open for under half a second to show that he never really intended to trade them.[17] But in the Banoczay complaint, the CFTC alleges a “median cancellation” time of 6.2 seconds—nearly 12.5 times longer than Coscia’s—in support of the same point. If, in the regulators’ mind, the timeframe that characterizes “spoofs” can stretch from under 0.5 seconds to over 6, there is no reasoned basis for them not to extend it further still—to say, 12.5 times 6 seconds (or well over a minute).

In the same way, the ASP gives zero guidance as to what events are permissible conditions on which an order cancellation may depend. As pointed out by others,[18] there are numerous reasons why a trader might expect to cancel an unfilled resting order. For example, an order could be placed with an intent to cancel it if the trader changes her mind, the market moves, a relevant news event occurs, she needs to leave the desk to attend a meeting, and so on.

Regardless of whether the intention is to cancel an unfilled order after a certain period of time or upon a certain event, the critical point is that this intention must be in a manual trader’s mind at the time the order is placed (explicitly or implicitly). There is no way it could not be.

As a result, every resting order that is not intended to be left open indefinitely violates the plain terms of the ASP.[19] This then gives law enforcement free reign to capriciously draw the line between legal and illegal trading. This is the definition of an unconstitutional law.[20]

Conclusion

Judge Lee is the only district court judge to rule that the ASP is constitutional as applied to manual traders and, in light of the above discussion, there are strong grounds to argue that his reasoning should not be followed. As such, if U.S. regulators continue to go after small overseas “spoofers” like the Banoczays, those targeted should not shy away from challenging them given the ASP’s inherent flaws.

[1] C.F.T.C. v. Banoczay, Jr. et al., 20-cv-05777, Dkt. #1 (Sept. 29, 2020 N.D. Ill.).

[2] Id. at 29.

[3] See Walter Pavlo, “After Conviction on ‘Spoofing,’ Defendant Questions His Previous Counsel’s Representation,” Forbes (Nov. 20, 2019) (discussing the Coscia case).

[4] See, e.g., United States v. Hayes, 118 F. Supp. 3d 620, 624-26 (S.D.N.Y. 2015) (explaining the contours of the fugitive disentitlement doctrine).

[5] The one possible exception is United States v. Radley, 659 F. Supp. 2d 803 (S.D. Tex. 2009), where criminal charges involving spoofing-type trading activity were dismissed in a decision subsequently affirmed by the Fifth Circuit. Note, however, that Radley did not implicate the ASP, since it occurred before the ASP was enacted.

[6] United States v. Bases, 18-cr-00048, Dkt. #301 (N.D. Ill. May 20, 2020).

[7] United States v. Coscia, 866 F.3d 782 (7th Cir. 2017).

[8] Id. at 794.

[9] Id. (emphasis in original).

[10] See Banoczay, 20-cv-05777, Dkt. #1 at ¶¶ 27-28 (explaining order book mechanics).

[11] 7 U.S.C. § 6c(a)(5); see also Coscia, 866 F.3d at 792 (concluding that the ASP’s parenthetical “clearly defines ‘spoofing’”).

[12] See Banoczay, 20-cv-05777, Dkt. #1 at ¶ 27; Brief of Amicus Curiae Futures Industry Assoc., Bases, 18-cr-00048, Dkt. #158 at 6 (“When an order has been accepted by the exchange system and matched with another order, the trade is final; it cannot be cancelled.”).

[13] For example, prosecutors presented evidence in the Coscia trial showing that only 0.5% of his alleged “spoofs” were filled. Coscia, 866 F.3d at 789.

[14] Id. at 16.

[15] 866 F.3d at 795.

[16] Antidisruptive Practices Authority, Commodity Exchange Act Release No. 3038-AD96 (May 20, 2013).

[17] Coscia, 866 F.3d at 789-90.

[18] See, e.g., Brief for Amici Curiae Jerry Markham and Ronald Filler (“Markham/Filler Brief”), Coscia v. United States, No. 17-1099 (Mar. 8, 2018) (“every [trader] intends to cancel trades before their execution for a broad range of reasons”).

[19] See Coscia, 866 F.3d at 797 (“[Coscia’s] scheme was deceitful because, at the time he placed the [spoof] orders, he intended to cancel the orders.”).

[20] See, e.g., F.C.C. v. Fox Television States, Inc., 132 S. Ct. 2307, 2317 (2012). (“A fundamental principle in our legal system is that laws which regulate persons or entities must give fair notice of conduct that is forbidden or required.”).