Andy Brooks is concerned about what he sees as inequities in stock markets. And as head of U.S. equity trading at T. Rowe Price Associates in Baltimore, he’s doing something about it.

The 33-year veteran of the T. Rowe trading desk has, for instance, taken on order routing practices, co-location of servers in the same facilities as exchanges’ matching engines, and “inaccessible” quotes and high cancellation rates in the halls of Congress, as recently as September.

“There is a growing distrust of the casino-like environment the marketplace has developed over the past decade,” he said in testimony before the Senate Committee on Banking’s Subcommittee on Securities, Insurance and Investment.

Brooks expressed concern to the subcommittee about the maker-taker model, payment for order flow and internalization of orders, as well as the widespread use of co-location, which he believes creates an uneven playing field between short-term traders and long-term investors. He also warned about the blurring of the lines between broker-dealers, which now match their own customers’ orders against each other’s, and exchanges, which match what orders are, in effect, left over.

In an interview with Traders Magazine, Brooks talked about the challenges market participants face, as well as his history at T. Rowe Price and the U.S. equities trading desk there.

“We’re concerned about the erosion of investor confidence, as well as the fact that the market seems to be out of balance in terms of its orientation toward investors-geared more toward those with very short time horizons, and less toward those whom the market was originally intended to serve,” he said. “We think it’s a very good time to bring the industry together and try and experiment with some ways that might make investors feel better about the marketplace and its commitment to everyone, in terms of transparency and disclosure, and equal opportunity.”

Brooks proposes creating a number of pilot programs to address issues as they are identified, which would then provide data and results that could be analyzed and assessed.

For instance, stock markets now operate on penny spreads, so-called decimalization. That can make it unprofitable to trade in companies whose shares are not widely traded. So one pilot program could test spreads of more than penny-three cents, five cents and 10 cents, for example. Many small companies need their stories told, and wider spreads might incent brokers to do that.

Another pilot program could eliminate inducements to order routing such as the maker-taker model, which rewards “makers” of liquidity with rebates on commissions and charges “takers” of same. This pilot would track the results of applying standard fees to both sides of a transaction.

Another program could reward market participants who take on obligations to make markets in specific stocks with preference in receiving order flow in the stocks they are handling. This would help make sure “their quotes are bigger, tighter and more real,” said Brooks.

Yet another program, tried so far in different forms by Direct Edge and Nasdaq, could charge a fee for each quote a firm generates past a certain threshold, to curb excess quotes that just get canceled. The threshold should be low enough to have impact and be the same across all exchanges, Brooks said.

“There’s been a lot of positive change over the last 15 to 20 years, but also some unintended consequences. Maybe some of things we all thought would be good haven’t been so good. Let’s step back and try to experiment and see if we can find some better solutions,” said Brooks.

Brooks believes “all of us have to reaffirm our obligation to protect the markets. What’s clear is that more people need to weigh in on the conversation.”

The buyside hasn’t generally done a good job in presenting its views to regulators to represent the interests of investors, he said.

“The high-frequency trading crowd has been very successful at presenting their side of things, that they’re the best thing since Mom and apple pie. The buyside has not been nearly as effective in suggesting perhaps the activities today aren’t as constructive as they should be,” he said.

Three Decades in Trading

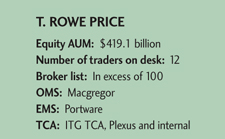

Brooks joined T. Rowe Price in 1980, a couple years out of college. He assumed his current role in 1992 and reports to Clive Williams, the global head of trading.

The biggest change in market conditions over Brooks’ career has been the speed at which trading decisions are implemented and market participants interact, he said. This, of course, is a consequence of the advance of technology in market operations.

The result has been an exponential increase in volume that an open-outcry system would not be able to handle, he said. “But,” he added, “the old system wouldn’t have had a flash crash.”

Some things haven’t changed, like the ability to identify good companies at cheap valuations, he said. That still is a good money manager’s stock, you might say, in trade.

“Trying to identify good companies that are mispriced to find great multicycle investments is an ongoing challenge,” he said.

Brooks runs a desk of 12 traders, divided into a large-cap desk and a small/midcap desk. Each trader is responsible for specific product lines and portfolio managers. Their secondary job is to be knowledgeable about particular Standard & Poor’s industry sectors, such as health care and energy.

“We utilize the sector responsibility to leverage our knowledge base and help us process information. It also allows our traders to get closer to our analysts,” Brooks said. “It’s important for traders to retain some ability to be a generalist. It’s important to have an awareness of different markets because you’ll be supporting and backing each other up.”

The traders work closely with the firm’s portfolio managers and analysts and “have a keen appreciation of what [the portfolio managers and analysts] are trying to accomplish,” Brooks said. “It’s important for traders to have a clear sense of mission. It’s easy to get in trouble in these markets if you don’t have a clear idea of what you are doing.”

The firm’s turnover is relatively low “and our trades tend to be incremental, but our people have made decisions, so the trading desk wants to be decisive, and we’re not afraid to do block trades,” said Brooks. “If we buy a stock that we like and it goes lower, our sense is to buy more.”

The trading team is not afraid of technology. Trading strategies take in both dark pools and algorithms. “We’re going to source liquidity wherever it resides,” he said. “Over the years we’ve tried to have an open mind about chatting with anybody who might provide liquidity or innovation in the marketplace.”

“But we’re concerned the market has become too complicated. It’s cluttered and confusing,” he added, with roughly 50 different equity venues, for instance, lit and dark. “We’re outsmarting ourselves with all of these different ways to trade. In the spirit of encouraging innovation, we’ve probably allowed too much competition, and it’s time to reassess.”

(c) 2012 Traders Magazine and SourceMedia, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.tradersmagazine.com http://www.sourcemedia.com/